Citizents of Georgia’s Sakartvelo (საქართველო) gathered in Tbilisi to mark one year since the start of mass protests. The demonstrations began in late November 2024, shortly after Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze announced the suspension of Georgia’s EU membership program.

This statement, following disputed parliamentary elections, sparked immediate public mobilization. During the first nights of protests, police used water cannons, tear gas, and pepper spray to disperse the crowds. Human rights organizations and media reported dozens of injured protesters and journalists, as well as over 300 arrests during the first week.

Over the past 12 months, the protest movement has not faded. Throughout the year, the authorities tightened their grip, introducing new restrictions on public gatherings, increasing fines, and initiating legal proceedings against activists.

Tensions remained particularly high ahead of local elections in October, which the opposition ultimately boycotted. The ruling Georgian Dream party won. Clashes between protesters, ruling party supporters, and police were reported in several locations. By late autumn, prosecutors had opened cases against a number of activists on charges related to “attempts to destabilize the state.”

While events unfolded on the streets of Georgia, a parallel information campaign was taking shape in Belarus. This report examines how Belarusian state media covered the Georgian protests over nearly two years—from early 2024 to late 2025—and identifies key narratives, manipulation techniques, and propaganda patterns.

Key findings

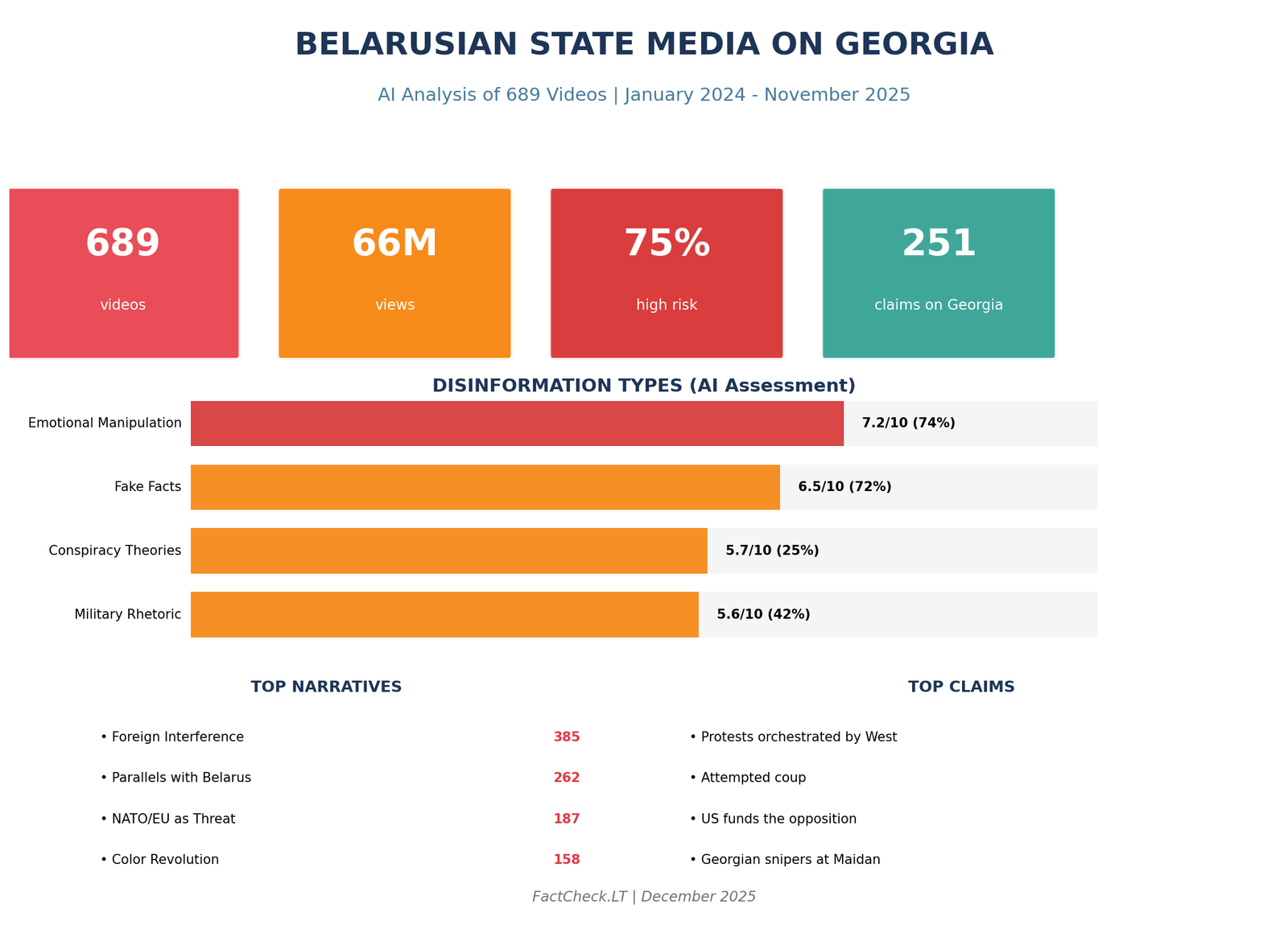

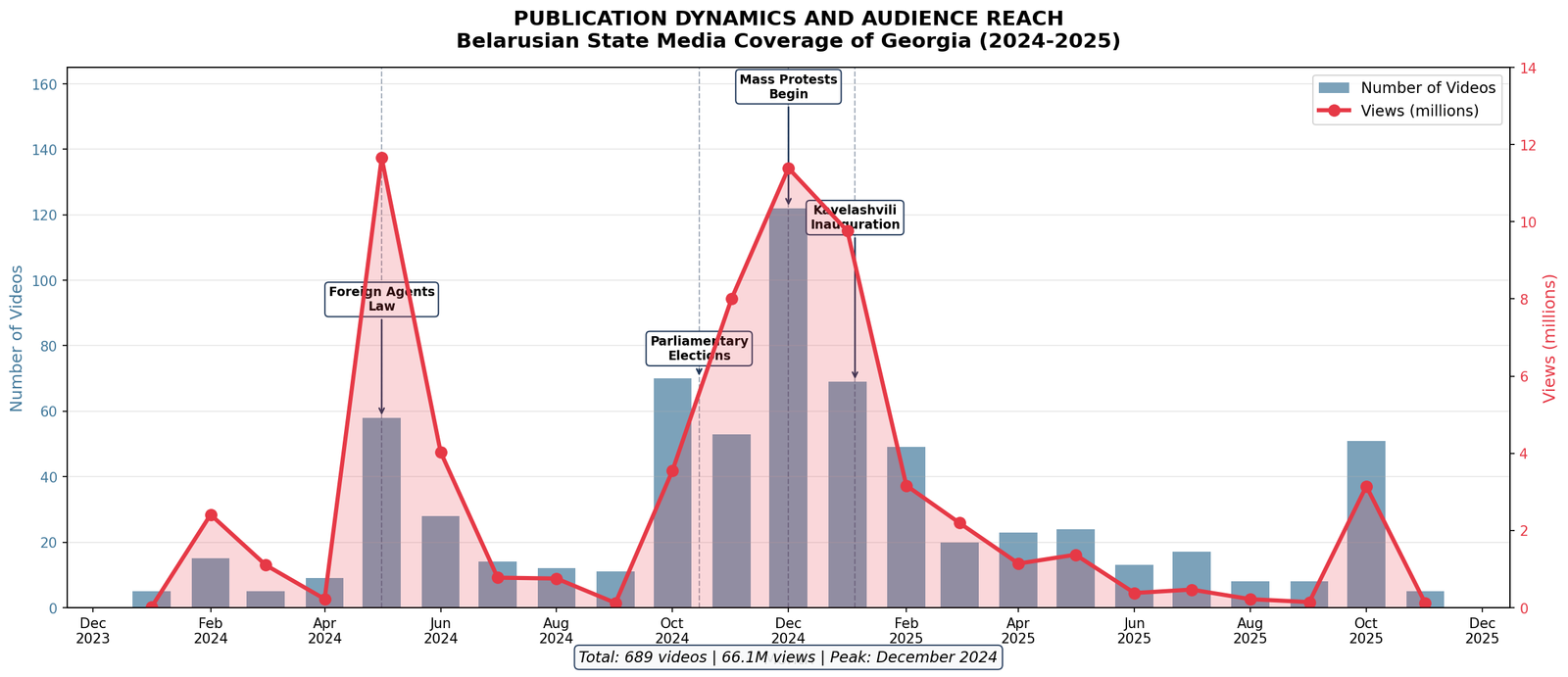

Our analysis covered 689 videos published by the five largest Belarusian state television channels on YouTube between January 2024 and November 2025. The total number of views exceeded 66 million. AI-based content analysis revealed that 75% of the videos exhibited a high or critical level of risk of disinformation, with emotional manipulation and unverified factual claims being the most common techniques.

Georgia ranked third among the most frequently attacked countries in this content—after Ukraine and the United States—indicating the significant role of the Tbilisi events in the overall strategy of Belarusian state media.

Methodology

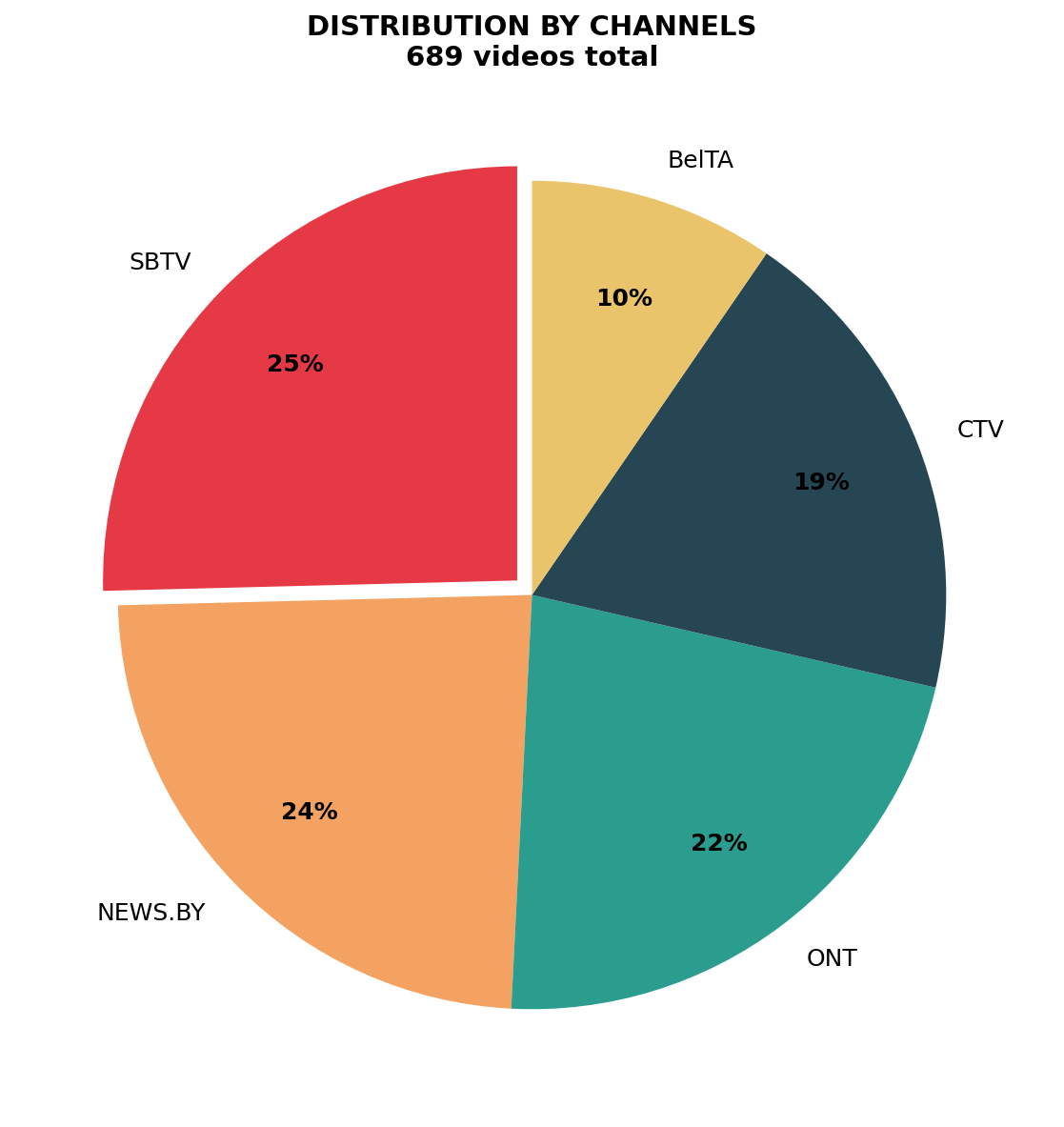

This dataset includes videos from five Belarusian state-run YouTube channels: SBTV (175 videos), NEWS.BY (164), ONT (153), CTV (131), and BelTA (66). All videos were selected using keywords related to Georgia and then filtered to exclude irrelevant content, such as travel vlogs and cultural programs.

Full transcripts were obtained for each video and processed using AI classification to assess the risk of disinformation, identify manipulation techniques, and extract specific claims. The analysis period spanned January 2024—when coverage of Georgia’s foreign agent law began to intensify—to November 2025, capturing the entire first year of the protest movement.

Timeline: Coverage intensity and key events

The volume of publications closely followed the developments in Georgia, with distinct peaks corresponding to major political events.

The first surge occurred in April-May 2024, when the Georgian parliament debated and ultimately passed the controversial Foreign Influence Transparency Law. During this period, Belarusian media released 67 videos, garnering nearly 12 million views. Coverage presented the law as a reasonable measure to protect national sovereignty, drawing clear parallels with similar legislation in the US and Russia.

A second, smaller peak occurred in October 2024 around the parliamentary elections. Coverage during this period emphasized the ruling party’s victory and characterized Western criticism of the vote as interference in Georgia’s internal affairs.

The most intense coverage occurred in November-December 2024, when protests erupted following the government’s decision to suspend EU accession negotiations. In December alone, Belarusian state-run television channels published 122 videos about Georgia—the highest monthly figure in the dataset—with over 11 million views. The tone shifted noticeably: protesters were increasingly described as “radicals” and “extremists” orchestrating a Western-backed coup attempt.

Timeline: How Lighting Has Changed

Phase 1: Foreign Agent Law (April-May 2024)

67 videos | 11.9 million views

The first wave of publications was linked to the adoption of a law on foreign influence transparency in Georgia. The main narrative: Georgia is defending its sovereignty from Western interference.

Top videos of the period:

- “Georgians Troll the European Union!” (SBTV) — 7.5 million views

- “Georgian authorities will not allow a Maidan in the country, similar to the Ukrainian scenario” (NEWS.BY) — 409,000 views

Typical context:

“They’re laughing in Georgia. I liked how the Georgian authorities responded to the Europeans. They said they’d suspend Georgia’s accession process to the EU. They responded…”

Phase 2: Parliamentary elections (October 2024)

70 videos | 3.5 million views

Election coverage has focused on contrasting the “correct choice” of the Georgian people with the “provocations” of the West.

Key messages:

- Victory of the Georgian Dream = rejection of war

- The opposition is financed from outside

- The West does not recognize democratic choice

Top videos:

- “Georgian citizens have rejected the pro-Western course!” (CTV) — 275,000 views

Phase 3: Mass protests (November-December 2024)

175 videos | 19.4 million views

The most intense period of coverage. The protests are being presented as an attempt at a “color revolution” similar to the Ukrainian scenario.

Top videos of the period:

- “Georgia’s Prime Minister Made a Shocking Statement!” (CTV) — 1.2 million views

- “Zurabishvili voluntarily resigns as President of Georgia” (CTV) — 1.1 million views

- THE FATE OF GEORGIA: election results, Zurabishvili’s despair, torchlit nights, the failed Maidan, the West’s wishes

Typical formulations:

“The opposition’s fourth attempt to stage a revolution in Georgia has failed.” “Western elites, contrary to the will of the Georgian people, are trying to advance their own interests.”

Phase 4: Continuation and “Lessons” (January-March 2025)

138 videos | 15.1 million views

Georgia is used as an example to warn Belarusian audiences about “Western scenarios.”

Typical context:

“We see what’s happening in Georgia… That’s why they’re still going to stir something up for you… Institutional organizers are smoothly moving toward you.”

- Mass Unrest in Georgia | The Crisis of Western Democracy | The Foreign Agent Law. Special Report

Phase 5: Anniversary (October-November 2025)

56 videos | 3.3 million views

Renewed interest in the topic in the context of the anniversary of the protests.

- Georgia is introducing strict regulations against protesters.

- The opposition staged protests in Tbilisi.

Assessing disinformation

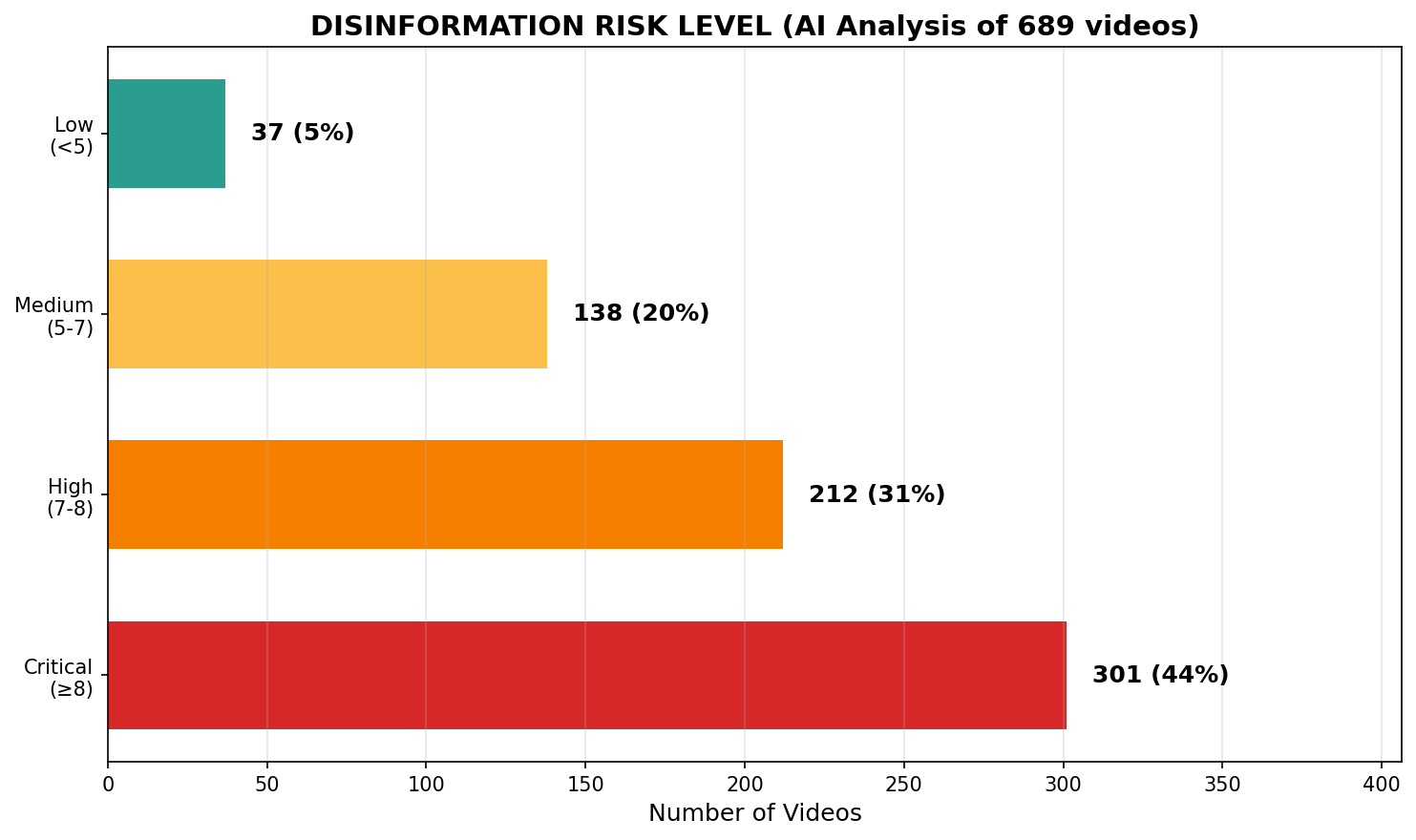

The AI analysis assigned each video a misinformation risk rating on a scale of 1 to 10.

The results show a dataset heavily skewed toward high-risk content: 44% of videos received a rating of 8 or higher (critical risk), while another 31% fell into the 7-8 range (high risk). Only 5% of videos were classified as low risk.

The results show a dataset heavily skewed toward high-risk content: 44% of videos received a rating of 8 or higher (critical risk), while another 31% fell into the 7-8 range (high risk). Only 5% of videos were classified as low risk.

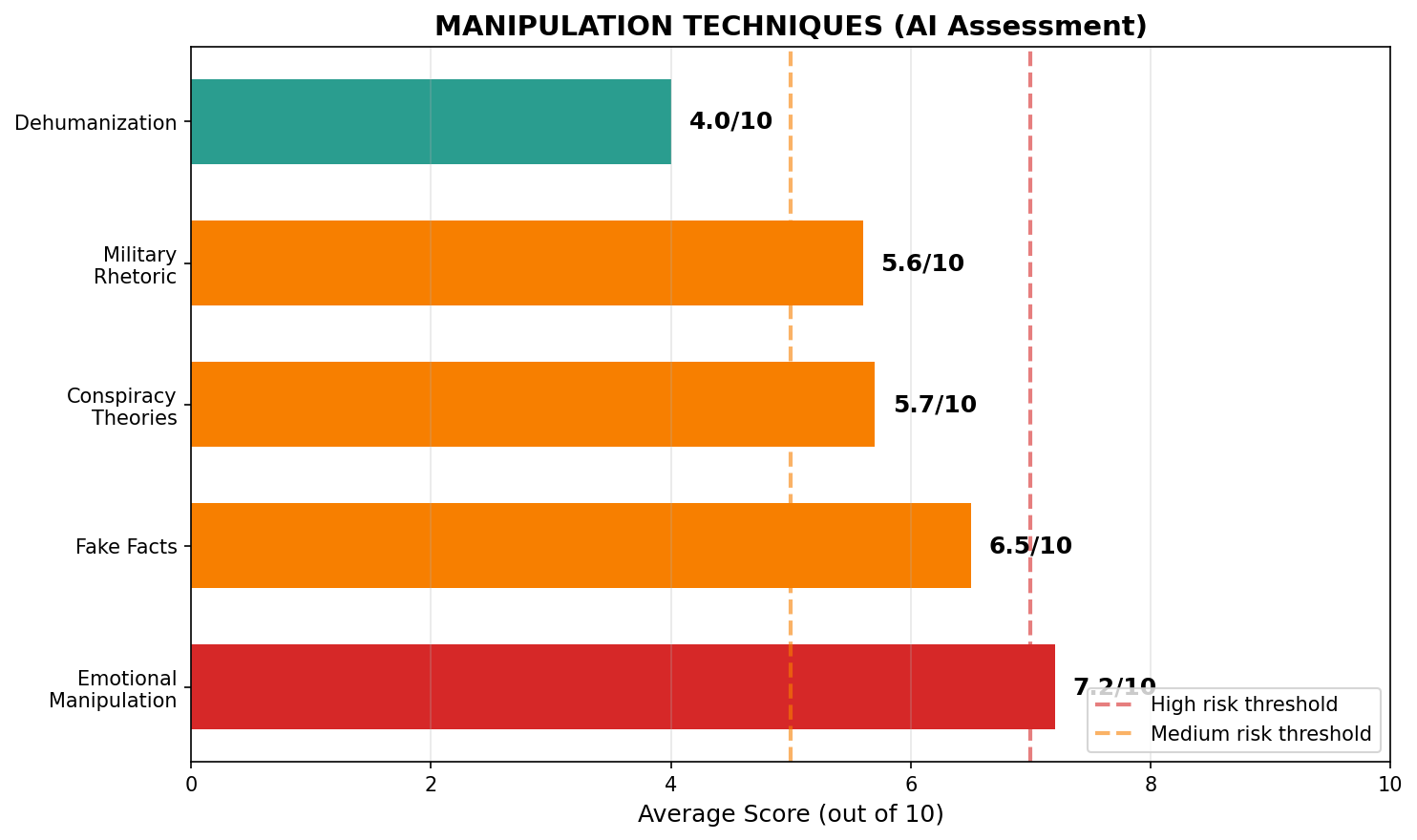

The most common manipulation technique was emotional manipulation, present at a high level in 74% of videos, with an average rating of 7.2 out of 10.

This category includes appeals to fear, dramatization, and alarmist sentiments about war and instability. False or unverified factual claims were found in 72% of videos, often presented without sources or context. Conspiracy narratives—about secret Western plots to destabilize Georgia—were found in a quarter of the content.

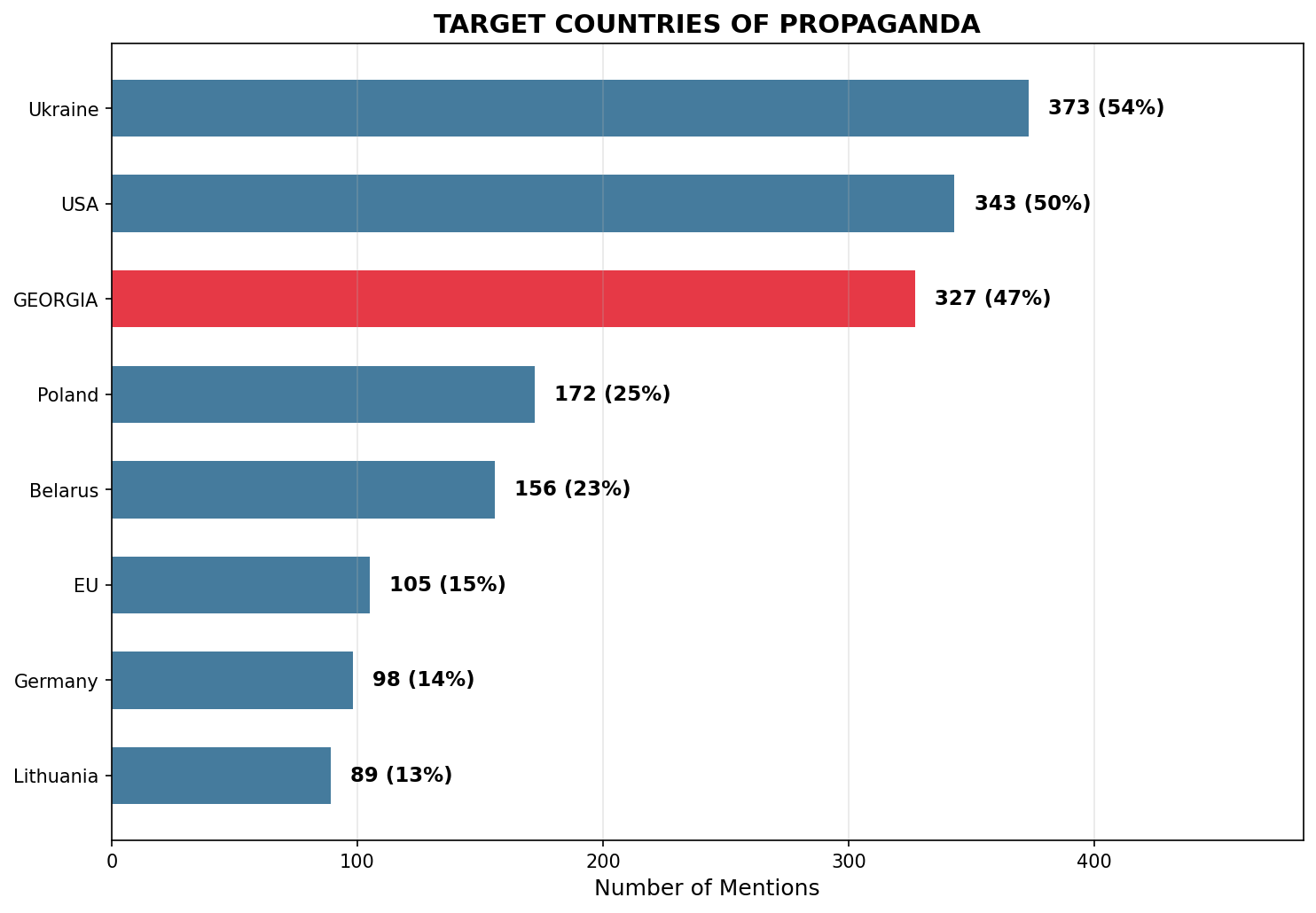

Target countries

Coverage of Georgia did not occur in isolation. An analysis of targets across all 689 videos shows that Ukraine remains the primary focus of hostile framing by Belarusian state media, appearing in 54% of videos. The United States follows with 50%, regularly portrayed as the architect of regional instability.

Georgia itself was mentioned as a target in 47% of the videos—an exceptionally high proportion, considering the dataset was already filtered for Georgian topics. This suggests that even in content nominally dedicated to Georgian events, the narrative often shifted to broader attacks against Western institutions and neighboring states.

Poland, Belarus, the European Union, Germany, and Lithuania also featured prominently, reflecting the regional reach of the propaganda messages.

Key narratives

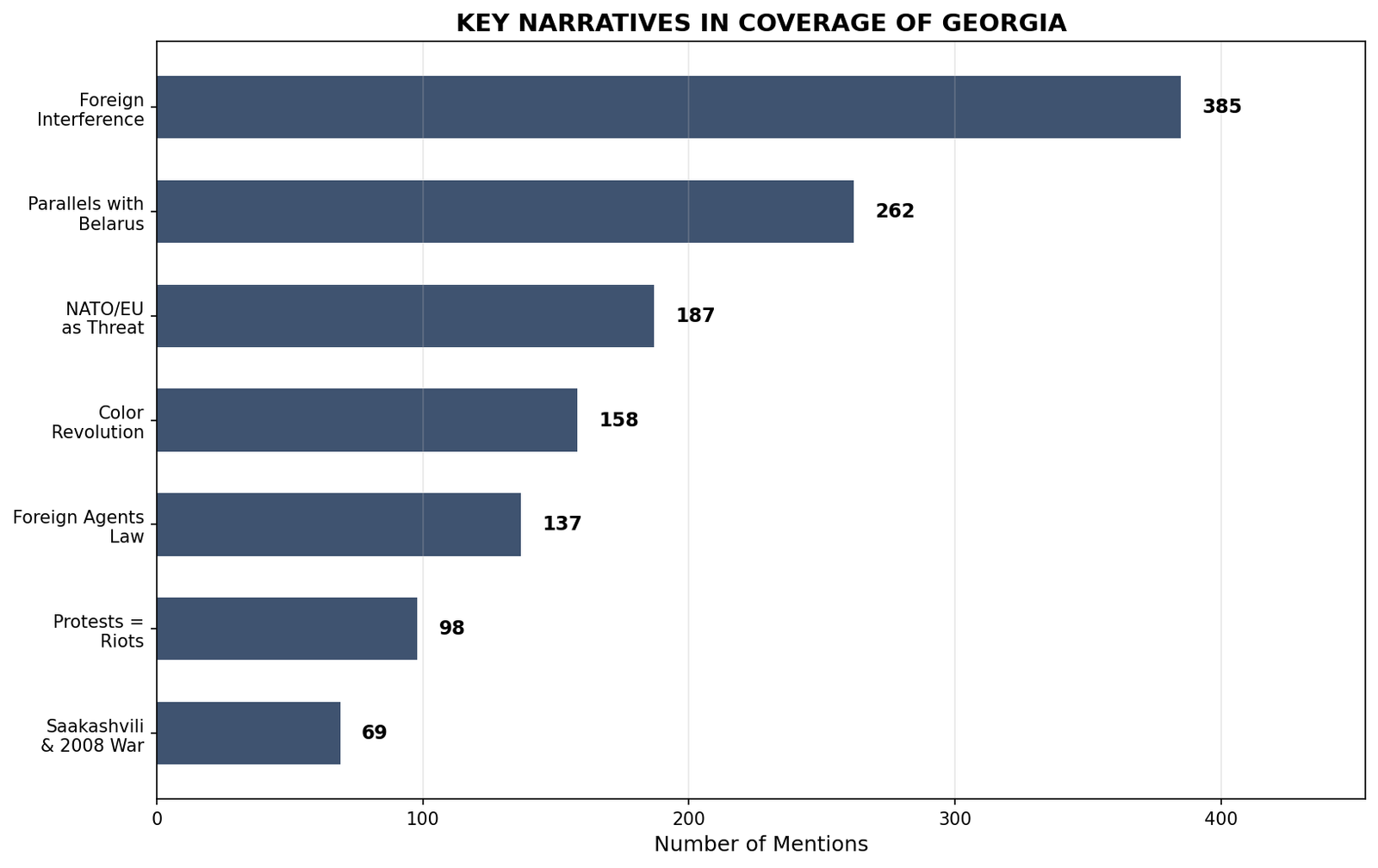

The analysis revealed seven distinct narrative clusters, each serving specific propaganda purposes.

Foreign intervention— by far the most common frame, appearing 385 times in the dataset. This narrative presents all protest activity as organized and financed from outside, denying the agency of Georgian citizens. Typical claims include allegations that the US State Department pays salaries to Georgian opposition figures and that NGOs serve as fronts for Western intelligence agencies.

Key points:

- The US is funding the opposition

- The West does not recognize elections if “their” candidates lose.

- NGOs – instruments of influence

Parallels with Belarusappeared 262 times. This narrative clearly links the Georgian events to the 2020 protests in Belarus, suggesting the same “scenario” will be used. The goal is twofold: to delegitimize the Georgian protesters through association and to remind Belarusian audiences of the regime’s narrative of its own repressions.

Examples:

“They’ve prepared much more seriously, the collective West, after Belarus’s failure.” “Institutional organizers are smoothly moving toward you.”

NATO/EU as a threat(187 mentions) presents European integration as a path to war and the loss of sovereignty. Coverage regularly cites the 2008 Russian-Georgian war as proof of the consequences of pro-Western policies, while simultaneously suggesting that EU membership will require Georgia to renounce its independence.

Examples:

- “Georgia’s dream of joining the EU is not yet destined to come true.”

- “Georgia is moving further away from the European Union, but closer to its own development path.”

Terminology“color revolution”appeared 158 times, drawing clear connections to the Ukrainian Maidan and other protest movements that authoritarian governments label as Western-sponsored coups. This framing delegitimizes mass protest as a form of political expression.

Examples:

- “The Georgian authorities will not allow a Maidan in the country based on the Ukrainian scenario.”

- “The situation in Georgia is a direct attempt at a color revolution, like in Belarus.”

Lightinglaw on foreign agents(137 references) consistently defended the legislation as a transparency measure, dismissing criticism as hypocrisy given similar laws in Western countries. This narrative omits key differences in application and context.

Typical argumentation:

Georgia’s ruling party called the US decision to impose sanctions against MPs unprecedented and comical.

Framing“protests = riots”(98 mentions) systematically reclassified peaceful demonstrations as violent riots. Protesters were labeled “radicals,” “extremists,” and “provocateurs,” while police violence was either ignored or justified as a necessary response.

Systematic use of negative language: “riots,” “pogroms,” “radicals,” “chaos.”

Headlines:

- “Georgia’s opposition is unleashing a war on the streets!”

- “Large-scale unrest in Georgia!”

- “Fierce fighting continues on the streets of Georgia!”

Saakashvili and the 2008 war(69 references) served as a historical reference point, with the former president portrayed as a cautionary tale of pro-Western leadership leading to military disaster.

Typical context:

“Saakashvili doesn’t care where he is! Georgia was pushed toward war with Russia.”

Claims requiring verification

AI analysis extracted 251 separate claims about Georgia from video transcripts.

The most frequently repeated include:

The claim that the protests in Georgia are organized by Western powers appeared in various forms throughout the dataset. Related claims indicated that the Georgian government receives funding directly from the US State Department, that NGOs act as intelligence fronts, and that protest leaders receive instructions from foreign embassies.

A particularly provocative claim—that Georgian snipers were responsible for the shooting of protesters during Ukraine’s 2014 Maidan—appeared in coverage linking the two countries’ protest movements. This claim has been repeatedly debunked, but continues to circulate in pro-Kremlin media.

Allegations of attempted coups and color revolutions portrayed legitimate political protest as a criminal conspiracy, while claims that the West “pushed Georgia into war” in 2008 upended the historical record of Russian military intervention.

Conclusions

The analysis shows that Belarusian state media’s coverage of Georgia served multiple propaganda purposes beyond simply reporting on events in Tbilisi.

First, the coverage functioned as a tool for legitimizing domestic repression. By presenting the Georgian protests as Western-backed attempts at destabilization, the narrative implicitly justified Belarus’s own repression of dissent in 2020 and subsequent years.

Second, Georgia served as a warning to Belarusian audiences. The message—repeated in hundreds of videos—was clear: this is what happens when citizens mobilize against their government, and this is what the West has planned for Belarus.

Third, the coverage supported Russia’s broader regional narrative of Western interference and the illegitimacy of pro-European political movements. The intensity of coverage and the consistency of messages across multiple state-run channels suggest coordination, not independent editorial decisions.

Finally, the timing and volume of publications demonstrate that Belarusian state media operate as a reactive propaganda apparatus, capable of quickly adapting coverage to evolving events and shaping audience perceptions.

The 66 million views garnered by this content represent a significant informational intervention, systematically distorting the reality of Georgian citizens exercising their democratic rights.

Data sources:

- Dataset: 689 videos, January 2024 – November 2025

- Channels: SBTV, NEWS.BY, ONT, CTV, BelTA

- Total reach: 66.1 million views

- Method: Full-text transcript analysis with AI classification

- Risk Assessment: Custom Misinformation Scoring Model (1-10 Scale)