TL;DR

Belarusian state and independent media cite such different speakers that they create two distinct realities. State media completely ignore Svetlana Tikhanovskaya (666 quotes in independent media, 0 in state media), Donald Trump (51 vs. 0), and the leaders of the Republic of Lithuania. However, they cite Viktor Orbán five times more often and promote an ecosystem of pro-Russian “experts” from Russia, Bulgaria, and Ukraine. The citation pattern demonstrates signs of coordinated information influence (FIMI): centralized speaker selection, synchronicity with Russian media, and characteristic “blind spots.”

Methodology

The study covers Belarusian media publications from 2025, divided into two dataset groups: over 72,000 publications from independent media and 77,000 from state-owned media. A total of approximately 40,000 quotes and 450,000 mentions were extracted from the 150,000 documents processed.

The analysis is based on two types of data. The first consists of direct and indirect quotes, where a specific person serves as the source of the statement. Constructions such as “stated,” “noted,” “according to,” as well as direct speech in quotation marks, were extracted. The second type consists of mentions, which record the appearance of a name in the text, regardless of whether the person is speaking or being spoken about.

This distinction is fundamental. Quotes reveal who the media gives a voice to, whose position they convey to the audience. Mentions reflect the significance of a person in the information field, even if they are deprived of the opportunity to speak. Political prisoners, for example, are rarely quoted, but are actively mentioned in independent media.

All names have been standardized: “Lukashenko,” “A. Lukashenko,” and “President of Belarus” are combined into a single person. False positives have been filtered out: names of organizations, unnamed positions, and geographic locations.

Tech stack

Data collection is carried out using the Oxylabs web scraper provided as part of the program.Project 4βfor research projects. Video content is transcribed via AssemblyAI, allowing YouTube to be included in the analysis alongside text sources. Named entity extraction is performed by the Natasha library, optimized for Russian-language texts, followed by normalization using a dictionary of over 200 rules. Semantic search and clustering are built on OpenAI vector embeddings stored in PostgreSQL with the pgvector extension. Analytical queries and visualization of speaker relationships are implemented in the Neo4j graph database, and Anthropic’s Sonnet and Opus models are used for contextualization and results interpretation.

Key observation: parallel realities

The Belarusian media landscape is divided into two virtually non-intersecting worlds. Independent and state-run media cite radically different speakers, giving audiences fundamentally different impressions of what’s happening.

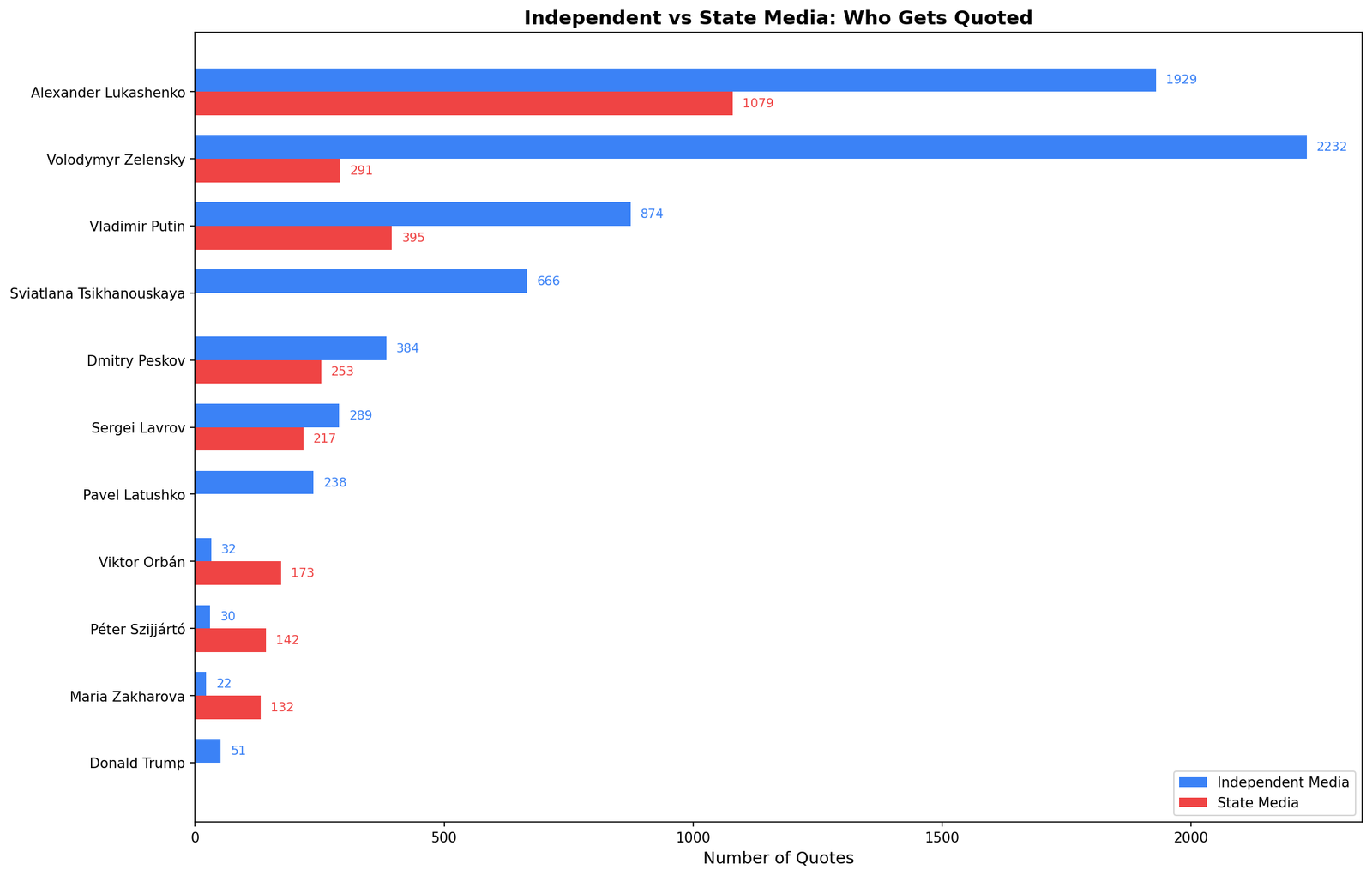

Volodymyr Zelenskyy ranks first in independent media with 2,232 quotes, while in state-run media he’s only third with 291. The difference is almost eightfold. Alexander Lukashenko leads state-run media with 1,079 quotes, accounting for approximately 20% of all citations, while independent media distribute attention more evenly among different speakers.

Invisible to state media

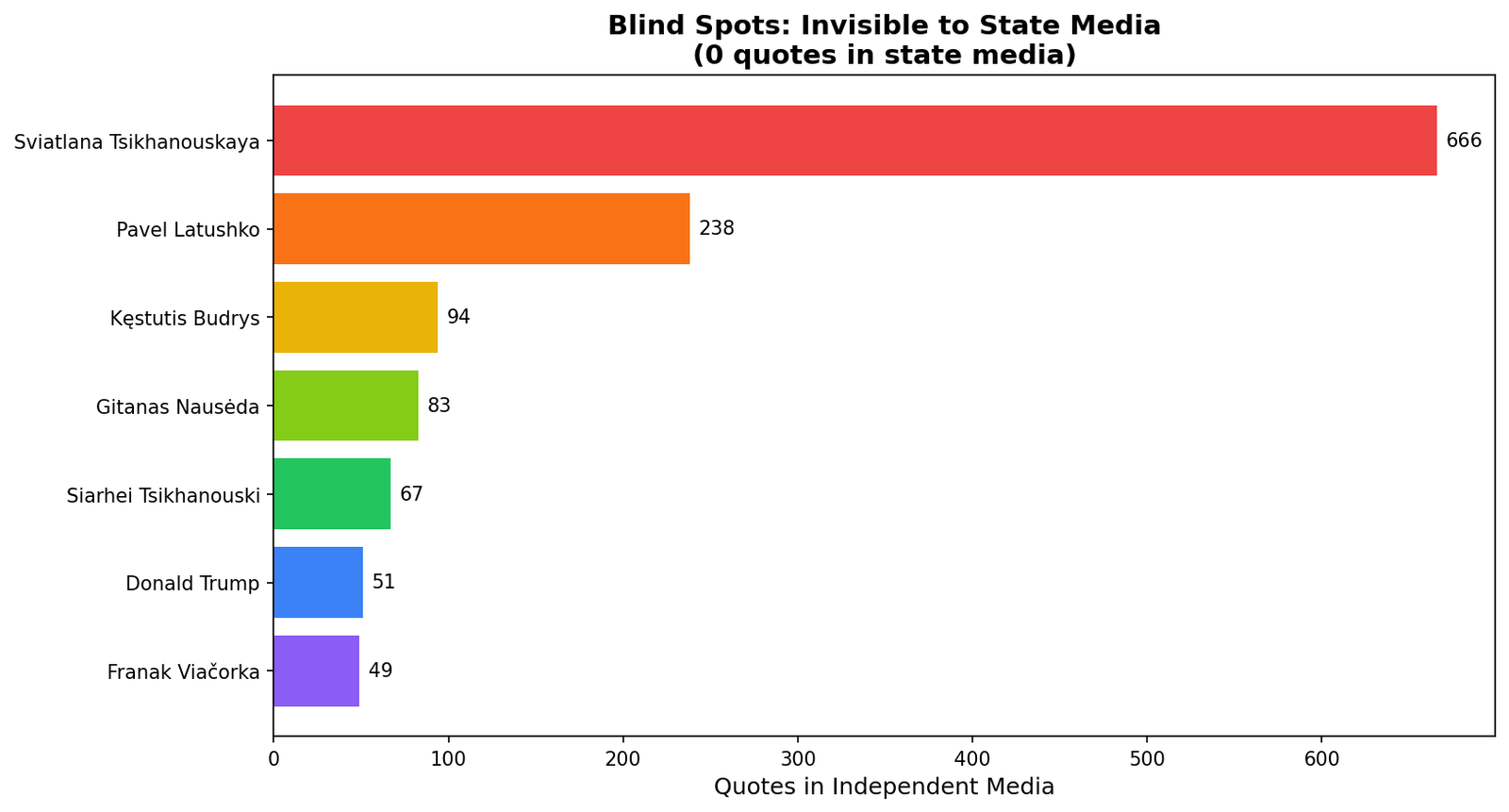

A whole host of significant political figures are completely absent from the state media landscape. Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, with 666 quotes in independent media, received not a single mention in state-run media. The situation is similar with Pavlo Latushko (238 quotes), Franak Vyachorka (49), Artem Shraibman (41), and other representatives of democratic forces.

The case of Donald Trump is particularly telling. The current US president has been quoted 51 times in independent media and not once in state-run media. For a country that positions itself as part of an anti-Western bloc, completely ignoring the American president appears to be a deliberate editorial policy.

The Lithuanian leadership is also under an information blackout. President Gitanas Nausėda (83 quotes in independent media), Foreign Minister Kęstutis Budrys (94), and other Lithuanian politicians are completely absent from state media, despite their geographic proximity and the significance of bilateral relations.

The Ukrainian military and political leadership, outside of Zelenskyy, exists only in the independent space. Commander-in-Chief Oleksandr Syrsky (55 quotes), intelligence chief Kyrylo Budanov (54), and former commander-in-chief Valeriy Zaluzhny (45) are not quoted by state media at all.

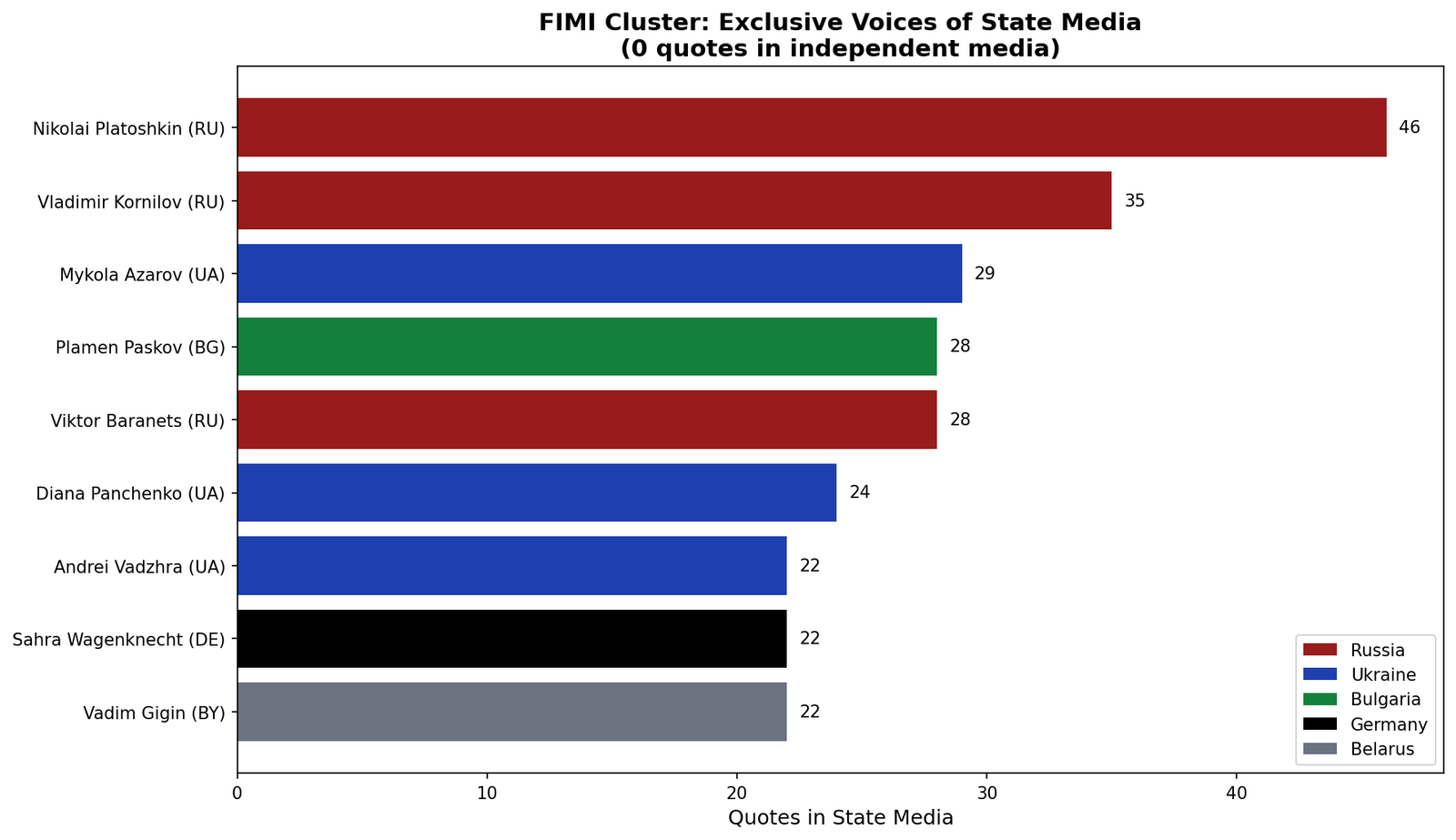

Exclusive voices of state media

State-run media are building their own ecosystem of experts and commentators unknown to independent media audiences. Nikolai Platoshkin, with 46 quotes, represents the Russian pseudo-opposition. Vladimir Kornilov (35 quotes) and Viktor Baranets (28) provide a Russian expert perspective. Plamen Paskov from Bulgaria (28 quotes) and Andrei Vajra from Ukraine (22) represent the international pro-Russian perspective.

A separate cluster consists of Belarusian ideologists and mid-level officials: Vadim Gigin (22 quotes), Sergei Banar (28), and Vladimir Karanik (28). These figures are virtually unknown to readers of independent media.

Of note is the presence of Sahra Wagenknecht (22 quotes), leader of the German left-wing party BSW, which criticizes support for Ukraine. Her voice reinforces the narrative of a split in the Western camp.

Hungarian vector

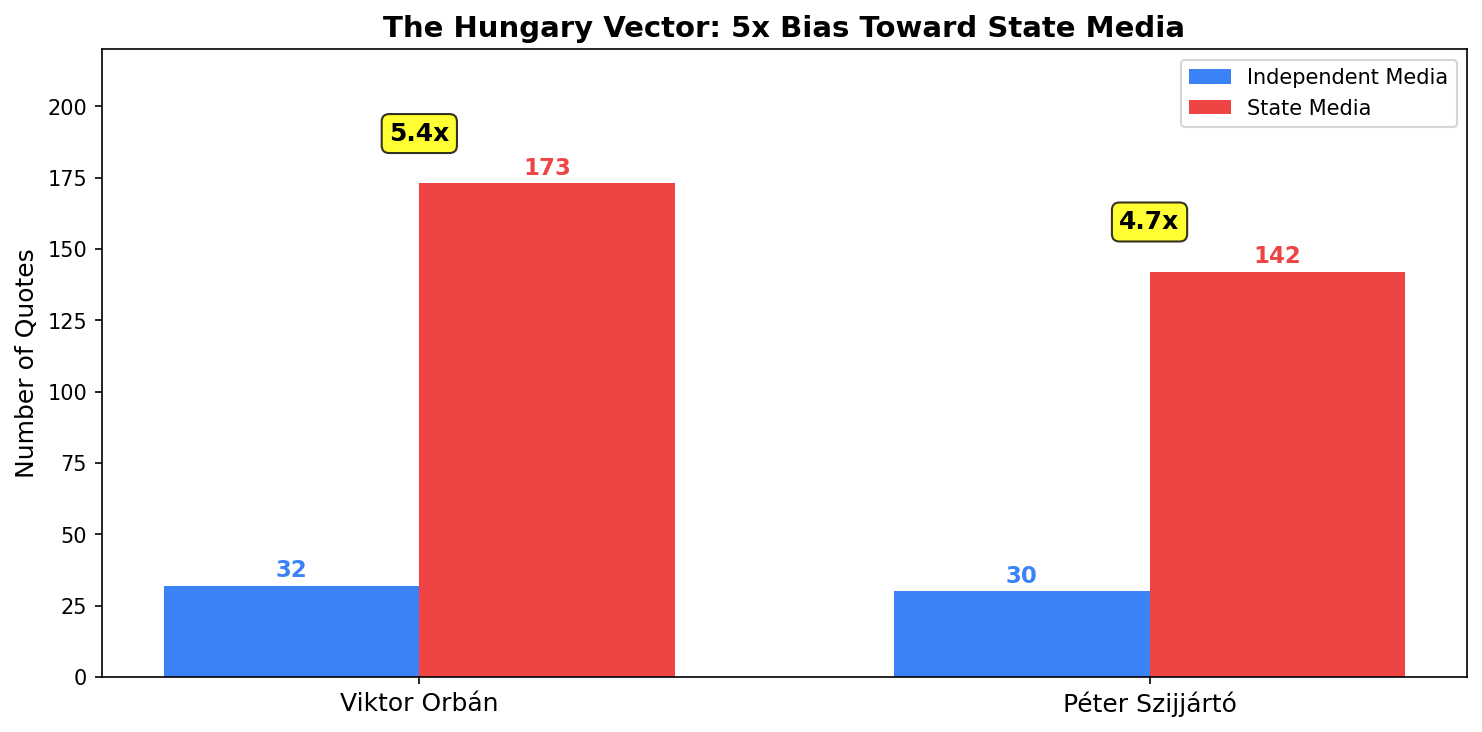

The most pronounced citation bias concerns Hungarian politicians. Viktor Orbán received 173 quotes in state-run media compared to 32 in independent media, a difference of more than fivefold. Péter Szijjártó is quoted 142 times in state-run media compared to only 30 times in independent media.

For the Belarusian state, Hungary plays the role of the “right” EU member, demonstrating the possibility of an alternative position within Western institutions. It is the only EU country whose leaders are actively promoted by state-run media.

Common space: Russian officials

The only category where a relative balance is observed is among top-tier Russian officials. Vladimir Putin is cited by both groups (874 times in independent media, 395 times in state-run media). Dmitry Peskov, Sergey Lavrov, and Yuri Ushakov are present in both categories, although with varying intensity.

This can be explained by the objective importance of Russia’s position for understanding regional processes. However, Maria Zakharova shows a sixfold bias toward state-run media (132 times versus 22 times), indicating her role as a propagandist rather than a diplomat.

Signs of coordinated information influence

The citation structure in Belarusian state media displays characteristic signs of FIMI (Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference), as defined in documents of the European External Action Service.

Traditional journalism involves drawing on a variety of sources, including representatives of various positions. Belarusian state media demonstrate a different approach: systematically promoting a narrow circle of commentators united not by expertise in specific fields, but by political loyalty to the Russian narrative.

Traditional journalism involves drawing on a variety of sources, including representatives of various positions. Belarusian state media demonstrate a different approach: systematically promoting a narrow circle of commentators united not by expertise in specific fields, but by political loyalty to the Russian narrative.

The analysis reveals three distinct clusters of voices present exclusively in the state media space.

First cluster The group is comprised of Russian “alternative experts.” Nikolai Platoshkin positions himself as an opposition politician, although his rhetoric completely aligns with the Kremlin line. Vladimir Kornilov and Viktor Baranets provide “expert” commentary that consistently supports the official Russian position. Yevgeny Spitsyn adds a historical narrative about the “unity of the Slavic peoples.” These figures are virtually unknown outside the propaganda circuit, but receive significant airtime in Belarusian state media.

Second cluster International voices with a pro-Russian stance are forming. Plamen Paskov from Bulgaria, Andrey Vajra and Diana Panchenko from Ukraine, and Mykola Azarov, as a representative of the ousted regime of Viktor Yanukovych, all create the illusion of broad international support for the Russian position. Their presence on airwaves is disproportionate to their actual influence in their own countries.

Third cluster presents European politicians critical of the EU’s mainstream position. Sahra Wagenknecht of Germany’s BSW party, Johann Wadephul, and Bart De Wever of Belgium are cited not as representatives of fringe positions, but as voices of “real Europe” opposed to “Brussels bureaucracy.”

Hungary plays a special role in this construction. Viktor Orbán and Péter Szijjártó receive a five-fold advantage in citations compared to independent media. Hungary is presented not simply as an ally, but as proof that EU and NATO membership is compatible with a pro-Russian stance. This is a critical element of the narrative aimed at a European audience: if Hungary can do this, then the problem isn’t Russia, but the “Russophobia” of the rest of Europe.

The coordinated nature of this system manifests itself in several dimensions. The same speakers appear simultaneously in Russian and Belarusian state media with identical talking points. Comments arrive with a characteristic delay of several hours after the original material is published in Russian sources. The range of topics promoted precisely corresponds to the priorities of Russian information policy: criticism of Western aid to Ukraine, a narrative of European fatigue with the conflict, and the promotion of negotiations on Russia’s terms.

At the same time, the system exhibits characteristic “blind spots.” The complete ignoring of Donald Trump, the current US president, cannot be explained by the editorial policy of a single outlet. This points to centralized agenda control: despite Trump’s statements potentially beneficial to the pro-Russian narrative, he does not fit into the established picture of the world, which portrays the US exclusively as a hostile force.

A similar explanation applies to the complete absence of Lithuanian officials. Lithuania is a close neighbor with which Belarus has real, albeit strained, relations. Zero citations of Lithuanian leadership are only possible through a deliberate editorial policy aimed at delegitimizing the neighboring state.

Conclusions

Citation analysis reveals not just editorial preferences, but the systematic construction of alternative realities. Readers of state-run media live in a world where the Belarusian opposition does not exist, Trump says nothing meaningful, Lithuania remains silent, and the main allies are Hungary and a circle of pro-Russian experts.

Readers of independent media get a picture where Ukrainian military and politicians are significant actors, democratic forces in Belarus retain a voice, and Western leaders from Lithuania to the United States shape the context of events.

These two information spaces intersect only at the inevitable point—the figures of Lukashenko, Putin, and senior Russian officials. Everything else exists in parallel universes.