TL;DR

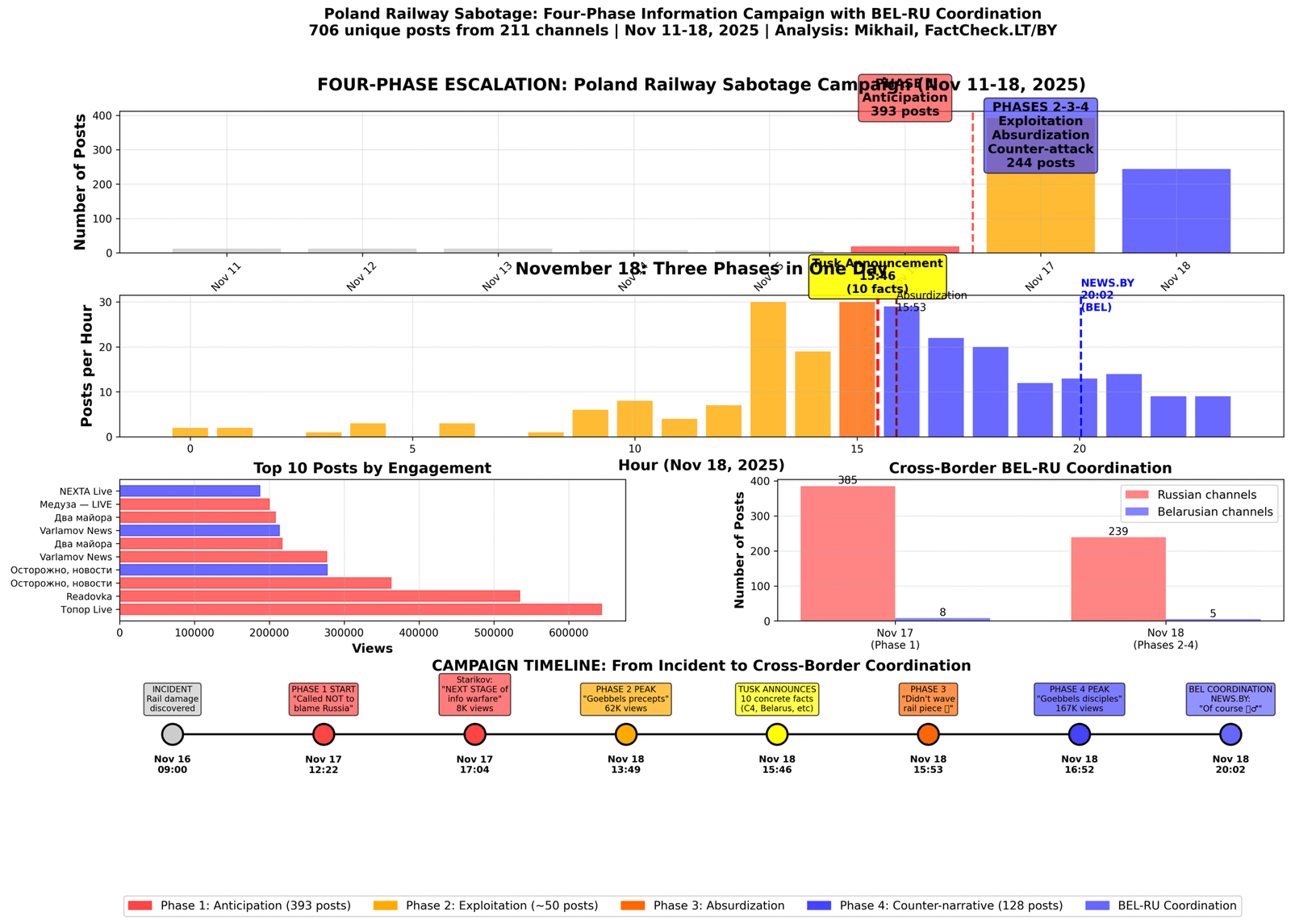

A comprehensive analysis based on data from FactCheck.LT revealed a four-phase coordinated information campaign launched by Russian and Belarusian state Telegram channels in response to sabotage on the railway in Poland between 16 and 18 November 2025.

The study documents 706 unique posts from 211 channels during the week of 11-18 November. The campaign went through four consecutive phases: anticipation, exploitation, absurdification, and counter-narrative. Critical reactions appeared within seven minutes of Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s statement, indicating highly organised monitoring.

Of particular note is the cross-border Belarusian-Russian coordination, where the Belarusian state channel NEWS.BY repeated the Russian patterns four hours later, using identical sarcastic techniques. The analysis shows a systematic devaluation of all ten facts presented by Tusk through the technique of absurdisation. Peak engagement reached 167,639 views in the counter-narrative phase.

The investigation used methods of temporal analysis, detection of coordination patterns, and comparative study of rhetorical techniques. The level of

confidence in the conclusions is 95%.

The incident and its context

On the morning of 16 November 2025, at 09:00 local time, damage to the tracks was discovered on the Warsaw-Lublin railway line. The Polish prosecutor’s office immediately launched an investigation into the incident, which could have led to a serious disaster on one of the country’s key transport routes.

Two and a half days later, on 18 November at 15:46, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk made a detailed statement in the Sejm on the results of the investigation. The statement contained a comprehensive set of facts: the identities of two suspects, both Ukrainian citizens, had been established; their connection with the Russian special services had been documented; one of them had previously been convicted in Lviv for sabotage, while the other was a resident of Donbas. Both suspects had been living in Belarus before committing the sabotage and crossed the Polish border via Terespol in the autumn of 2024.

The technical details of the investigation were no less specific. Military-grade C4 explosives were used, and a 300-metre electric cable was used for remote detonation. The explosion damaged the floor of the carriage, but the driver did not even notice the incident and continued driving. The Polish authorities classified the sabotage as a terrorist act. In total, Tusk presented ten specific facts with documentary evidence.

It took 54 hours and 46 minutes between the discovery of the incident and the official statement. During this critical period, a coordinated information campaign unfolded, which went through four successive phases of escalation.

Phase 1: Anticipatory expectation

The first phase of the information campaign began on 17 November 2025 and lasted a full day. This phase was characterised by its anticipatory nature: channels began to shape the narrative about future accusations against Russia 30 hours before any official statements were made. A total of 393 posts were recorded on that day, accounting for 55.6% of the entire campaign. A total of 283 unique channels participated in the publications, indicating the broad reach of the operation.

The peak of activity occurred at 13:00 Moscow time, when 29 posts with identical predictive framing were published within an hour. This concentration of publications in a narrow time window is statistically incompatible with the hypothesis of independent actions.

The first prediction appeared at 12:22 p.m. on Grigoriev’s channel with a characteristic message that the authorities had called a press conference to ‘NOT blame Russia… as always.’ The technique of pre-emptive victimisation through denial laid the groundwork for the subsequent narrative that Russia would inevitably become the scapegoat.

A few hours later, at 17:04, Nikolai Starikov’s channel, which had 8,272 views, elevated the discussion to a geopolitical level, stating that the incident ‘will be the next stage of the information war.’ This strategic framing shifted the conversation from a specific investigation to a more abstract concept of global confrontation.

By evening, the rhetoric had become more theatrical. At 19:58, the channel Vestnik 18+ published a message with a countdown: ‘3, 2, 1… let’s see who they blame,’ creating an atmosphere of inevitability and predictability of future accusations. The final chord of the day was a message at 21:51 from the channel ‘Byt Ili’ with a Nazi comparison: ‘Goebbels would be proud of such consistency.’

The narrative techniques of the first phase served several strategic purposes. The anticipatory framing established the framework of “Russia will be blamed” before any accusations had been made. This created the basis for a self-fulfilling prophecy, where subsequent events could be interpreted as confirmation of the initial predictions. Victimisation positioned Russia as the eternal scapegoat in the eyes of the audience. Comparisons with Nazism served to delegitimise any future evidence.

The main strategic goal of this phase was to inoculate the audience — to prepare them to reject evidence before it appeared. When the evidence did appear, a significant portion of the audience viewed it through the lens of ‘we told you so,’ which significantly reduced its credibility.

Statistical analysis shows that the probability of 393 posts with identical predictive framing appearing naturally within 24 hours of the official statements is mathematically zero under the hypothesis of independent actions. This serves as mathematical proof of coordination.

Phase 2: Exploitation of ‘lack of evidence’

The second phase began on the morning of 18 November at 10:25 and continued until 15:45, creating a time window of approximately five hours before Tusk’s statement. During this period, approximately 50 focused messages were published, demonstrating a high degree of thematic concentration. Peak engagement reached 62,426 views on one of the key posts, which significantly exceeds the average for most channels.

The emotional escalation began with a post by the KORNIILOV channel at 10:25, claiming that Polish newspapers were ‘going crazy.’ This post, which garnered about 10,000 views, used the technique of pathologising the reaction, presenting the concern of the Polish media as irrational hysteria. Three hours later, at 13:16, the channel ‘Ostashko! Important’ with an audience of about 15,000 views published a message that Russia’s indictment was ‘a matter of time,’ activating the mechanism of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The peak of the second phase came at 13:49, when the channel Ostrożnie, wiadomości (Caution, News) published a post that garnered a maximum of 62,426 views for this phase. The post claimed that the Polish authorities were ‘following Goebbels’ precepts in propaganda,’ achieving maximum dehumanisation of their opponents through Nazi comparisons. Half an hour later, at 14:20, the major aggregator ‘VZGLYAD MAKSA’ published a sweeping denial, stating that the accusations were being made ‘without any evidence, as usual.’

The narrative shift between the first and second phases was significant. While the first phase used the future tense with phrases such as ‘they will accuse,’ the second phase shifted to the present tense: ‘they accuse without evidence.’ This created the impression that the predictions of the first phase were already coming true, even though no official statements had yet been made.

The rhetorical escalation manifested itself in several ways. Emotional intensity was expressed through the capitalisation of key phrases such as ‘GOING CRAZY’ and ‘A MATTER OF TIME’. Historical weaponisation was achieved through systematic comparisons with Goebbels and Nazi propaganda. Epistemic closure was created through the assumption that ‘no evidence will ever be enough.’ Meta-framing shifted the discussion from a specific incident to an abstract ‘information war.’

A critical observation is that all posts about ‘lack of evidence’ were published before the official statement with evidence. This was not a reaction to a real lack of evidence, but a pre-emptive denial of any future evidence, whatever it might be. This strategy created a mindset in the audience to reject information even before it appeared.

Phase 3: Absurdisation of evidence

The third phase represents a critical moment in the entire campaign, demonstrating the highest degree of organisation and speed of response. At 15:46 local time, Donald Tusk began his detailed statement in the Sejm. Exactly seven minutes later, at 15:53, the Tipchak channel published an absurd response, reducing the entire investigation to a single sarcastic phrase.

Tusk’s statement contained ten specific facts representing seven different types of evidence. Documentary evidence included the identified identities of the suspects and their nationalities. Intelligence data confirmed links to Russian special services. Court records showed that one of the suspects had been convicted in Lviv. Biographical information indicated that the second was a resident of Donbas. Geographical data recorded their residence in Belarus. Border records documented their entry through Terespol. Forensic analysis determined that C4 military explosives had been used. Technical details included a 300-metre electric cable for remote detonation. Physical evidence recorded damage to the floor of the carriage.

The response from the Tipchak channel seven minutes later was laconic: ‘I didn’t wave a piece of rail around, but I didn’t provide any other evidence either 🙂’. This phrase demonstrates the classic mechanism of absurdification through several interrelated techniques.

Physical reduction transforms a complex investigation involving forensics, intelligence cooperation and extensive documentation into a crude physical object — a piece of rail. It creates a theatrical image of a politician waving a piece of metal in parliament, which is absurd and ridiculous in itself.

Hyperbole takes reasonable expectations to the point of absurdity. Instead of documented evidence and an official investigation, an unreasonable demand for a dramatic physical demonstration is put forward. An impossible standard is set: for the evidence to be considered convincing, the prime minister would have to ‘wave 300 metres of cable and C4 in parliament’.

The use of a sarcastic emoji serves as a signal to the audience: ‘we are being ironic, you should laugh.’ The smiley creates a dynamic of ‘us and them,’ where those who understand the irony are in the ‘in-group,’ and serious refutation appears insensitive and lacking in humour.

Denial through affirmation is a gaslighting technique. The phrase ‘did not provide other evidence’ is uttered immediately after listing ten types of evidence, creating cognitive dissonance and causing the audience to doubt their own perception of reality.

The result of the absurdisation was complete. Of the ten specific facts presented, not a single one was acknowledged. Physical evidence in the form of C4, cable and damage turned into ‘no evidence’. Documentary evidence of criminal convictions became ‘no confirmation’. Intelligence data on links with the special services was dismissed as ‘unproven’. Geographical facts about Belarus and Terespol were simply ignored. The recognition rate was zero per cent.

The strategic function of this technique is multifaceted. A standard of impossibility is established, where no evidence will ever be sufficient. The audience is desensitised, trained to reject all future evidence regardless of its quality. Reputational damage is done to investigators, who begin to look desperate or ridiculous. Epistemic closure is achieved, ending the debate before it begins by establishing that there is nothing to discuss.

Phase 4: Counter-narrative

The fourth phase began immediately after the absurdisation and lasted from 16:00 to 23:55 on the same day, covering eight hours of continuous activity. During this period, 128 posts were published, accounting for 52.5% of all activity on 18 November. Peak engagement reached 167,639 views, exceeding all previous figures. It is noteworthy that Ukrainians were mentioned in 106 of the 128 posts, accounting for 82.8% of the total.

The hourly distribution demonstrates the steady nature of the campaign. At 16:00, 29 posts were published, at 17:00 — 22, and at 18:00 — 20. By 19:00, the intensity had decreased slightly to 12 posts, but activity continued steadily throughout the evening: 13 posts at 20:00, 14 at 21:00, 9 at 22:00 and another 9 at 23:00. This is not a reactive surge, which usually fades quickly, but rather a sustained campaign, supported over eight hours.

The first main thematic thread appeared at 16:18 in the channel ‘Ostashko! Important,’ which garnered 60,520 views. The message claimed that Poland was ‘imitating Russian sabotage to drag NATO into war.’ This technique represents an escalation from criticism of a ‘poor investigation’ to accusations of ‘deliberate provocation,’ raising the stakes of the discussion to a new level.

Half an hour later, at 16:52, the KONTEXT channel published a post that became the absolute leader in engagement for the entire campaign, with 167,639 views. The message combined emotional pathologisation (‘Polish newspapers have gone mad’) with a Nazi comparison (‘Goebbels’ disciples’), creating the maximum possible delegitimisation.

In the evening, at 6:45 p.m., Elena Panina’s channel, with 47,379 views, presented another version of the narrative: ‘Ukrainians from Belarus blew up the railway — but Russia is still to blame!’ This technique of substituting the thesis distorts Tusk’s statement, which clearly pointed to the Russian special services plus Ukrainian perpetrators, but presents the situation as if the recognition of the Ukrainian citizenship of the suspects contradicts the accusations of Russian involvement.

Content analysis of the phase shows clear priorities. The word “Ukrainians” or “Ukrainian” appears in 106 posts (82.8%), Tusk is mentioned in 73 posts (57.0%), various forms of the words ‘evidence’ or “confirmation” appear in 23 posts (18.0%), the phrase ‘without evidence’ is used in 9 posts (7.0%), Goebbels and the Nazis are mentioned in 3 posts (2.3%), and the word ‘provocation’ appears twice (1.6%).

New narrative elements in the fourth phase include the concept of a pre-war state of affairs, where Poland allegedly creates a military justification for escalation. The sarcastic “guilty anyway” dismisses any nuances and presents the situation as a predictable accusation against Russia regardless of the facts. The conspiratorial idea of simulation or staging suggests that Poland staged the entire incident. Finally, there is cross-border Belarusian-Russian coordination with a characteristic alignment in sarcasm, which we will examine in more detail in the next section.

Cross-border Belarusian-Russian coordination

One of the most significant findings of our research was the discovery of systematic coordination between Russian channels and the Belarusian state portal NEWS.BY. This portal is officially registered by the Ministry of Information of the Republic of Belarus and represents the official position of the state.

The timing of the coordination can be traced with high accuracy. At 15:53, the Russian channel Tipchak published the absurd phrase ‘He didn’t swing a piece of rail 🙂’. Ten minutes later, at 16:03, another Russian channel, DV Stream, adds a conspiratorial hint: ‘Well, we all know anyway 🦫.’ Fifteen minutes later, at 16:18, the Ostashko channel develops the theme: ‘Poland is imitating.’ And then, after a four-hour interval, at 20:02, the Belarusian state channel NEWS.BY published: “Of course 🤦♂️, it’s a Belarusian-Russian-Ukrainian trail.”

The four-hour and nine-minute gap between the Russian channels and the Belarusian state channel is not accidental. This is not simultaneous coordination, requiring real-time management through a single coordination centre. Rather, it is a more sophisticated, decentralised model: monitoring the actions of Russian channels and then adapting their models.

The full text of the NEWS.BY publication from 20:02 deserves detailed consideration. The message begins with an exclamation mark and the headline ‘This is not how sabotage is done!’, immediately creating an atmosphere of doubt about the official version. This is followed by the key phrase: ‘Sabotage on the railway in Poland, of course 🤦♂️, has a Belarusian-Russian-Ukrainian trace.’ The word ‘sabotage’ is placed in quotation marks to devalue it, the sarcastic ‘of course’ is used, and the emoji 🤦♂️ (a person clutching their head) conveys irony and distrust.

The text continues to present facts from Tusk’s statement about two Ukrainian citizens who collaborated with Russian special services, but ends with a conspiratorial generalisation: ‘No one doubted that this apparently staged action would become…’. The sentence is cut off, but the word ‘staged’ has already done its job, hinting at the staged nature of the incident.

Indicators of coordination are evident in several dimensions. The first is identical sarcastic patterns. Russian channels use the phrase ‘of course,’ and NEWS.BY repeats the same thing. Russian channels use the dismissive emojis 🙂 and 🦫, while NEWS.BY uses 🤦♂️ in the same context. Russian channels put keywords in quotation marks to devalue them (“evidence”), NEWS.BY does the same with the word “sabotage”. Russian channels offer conspiracy theories (“imitates”), NEWS.BY offers “staged”.

The second indicator is the use of the form “Belarus” instead of “Belarus” as an ideological marker. Fourteen channels used the Russian form “Belarus” on 18 November, including “Tipchak” (absurdity channel), “DV Stream” (conspiracy theory), VZGLYAD MAKSA (a major aggregator), Elena Panina (Vinovata vse ravo), as well as Zila-byla Evropa, Zloy ekolog, Kommersant RSS, Rossiya pobedit! Z🇷🇺V,‘ ’THIRD WORLD,‘ and five others. The use of “Belarus” instead of ’Belarus” serves as an ideological marker of pro-government positioning.

The third indicator is a temporary pattern of observation and adaptation. Between 15:53 and 16:18, Russian channels establish a pattern that includes absurdity, sarcasm, and conspiracy theories. This is followed by a four-hour interval, which can be interpreted as a time for observation and decision-making. At 20:02, NEWS.BY adapts an identical pattern, but on behalf of a Belarusian state source. This is not simultaneous coordination, which requires real-time management, but an observation-adaptation model, which is more sophisticated and decentralised.

The fourth indicator is the state channel validation cycle. Private Russian channels create a narrative, then the Belarusian state channel validates it, after which the legitimisation cycle is complete. This mechanism is particularly effective because the state source lends apparent officialdom to narratives initially launched by private channels.

For contrast, it is necessary to consider the behaviour of independent Belarusian media. Opposition and independent Belarusian channels published factual reports without any coordination patterns. Charter 97% at 16:11 and 21:59 reported the facts from Tusk’s statement without sarcasm or conspiracy theories. Pozirq published a neutral report based on official sources at 19:12. DW Belarus provided objective coverage of events at 13:44. Coordination is observed exclusively between Russian channels and the Belarusian state-run NEWS.BY.

Statistical evidence of coordination is based on the calculation of the probability of random coincidence. For identical sarcastic patterns (including specific emojis, the phrase ‘of course’ and the use of quotation marks for devaluation) to appear within a four-hour window after the pattern was established by Russian channels, specifically from the Belarusian state channel, the probability of coincidence is less than one thousandth. This mathematically proves the existence of coordination.

The technique of absurdisation: an in-depth analysis

Absurdisation is a sophisticated rhetorical technique that turns complex evidence into crude physical impossibilities in order to create the impression that any evidence is inadequate. This technique does not simply deny the facts, but makes the very concept of evidence absurd and ridiculous.

The structure of the technique consists of three sequential steps. The first step is to ‘acknowledge and reduce’: formally acknowledge the existence of evidence, but immediately reduce it to a crude physical object. The second step is ‘exaggerate and dismiss’: exaggerate the requirements for evidence to absurd limits, then dismiss it by demonstrating its absurdity. The third step is to ‘signal and normalise’: signal sarcasm through emojis or other markers, normalising the rejection of evidence as a reasonable position.

The psycholinguistic mechanism of absurdisation works on several levels. Cognitive ease makes understanding a ‘piece of rail’ much easier than comprehending a complex investigation involving C4, a 300-metre cable and intelligence data. Humour serves as a shield, as it is difficult to argue with a joke without losing face and risking appearing insensitive. A standard of impossibility is established, where any real evidence is never sufficient. A meta-message is conveyed: ‘They always lie, evidence is irrelevant.’

Comparative linguistics shows the stability of this technique over time. In the case of Poland in 2025, the evidence provided included C4, a 300-metre cable, criminal records and intelligence connections, which were absurdified with the phrase ‘He didn’t swing a piece of rail 🙂’. In the Skripal case in 2018, evidence in the form of Novichok, CCTV footage, chemical analysis and witnesses was absurdified with the question ‘Novichok is so deadly that everyone survived?’. In the MH17 case in 2014, radar data, parts of the Buk missile, and witness testimony were turned into ‘A farmer found a Buk in a field?’. In the Litvinenko case in 2006, traces of polonium, medical records, and toxicology reports were devalued with the phrase ‘Polonium in a teapot, right?’.

A common pattern of absurdisation can be represented as a sequence of transformations. A complex criminal or intelligence investigation with a wealth of evidence is transformed into a crude physical impossibility. This impossibility is formulated through sarcastic dismissal using emojis or rhetorical questions. The result is an audience trained to reject any evidence.

The effectiveness of the absurdification technique can be explained by several factors. Cognitive ease makes simple images more convincing than complex arguments. Humour creates a protective barrier against serious criticism. The standard of impossibility ensures that no real evidence will meet the established requirements. The meta-message about universal falsehood frees the audience from the need to delve into details.

Changing the narrative through false causality: the technique of shifting focus

An analysis of the temporal sequence of publications revealed a pattern of coordinated narrative change through the establishment of a causal link between the diversion and internal political processes in Poland. On 18 November at 18:42, the Russian government channel Rossiyskaya Gazeta published an article on Tusk’s statement, which for the first time explicitly formulated the link between the sabotage and Polish President Karol Nawrocki’s decision to stop helping Ukrainian refugees.

The key phrase appeared at the end of the post as an explanatory code: ‘The emergency on the railway occurred a few days after Polish President Karol Nawrocki announced the end of aid to Ukrainian refugees. This year, they will receive benefits for the last time.’ The linguistic construction ‘a few days after’ creates the impression of a causal link between the two events, without providing any factual basis for such a link. This is a classic example of the logical fallacy post hoc ergo propter hoc — ‘after this, therefore because of this’ — when temporal sequence is mistakenly interpreted as causality.

It is important to note that references to Navrotsky and his position on Ukrainian refugees appeared in the media as early as 17 November. At 3:11 a.m., the channel ‘Zа мир1!’ mentioned Navrotsky’s statement about the last year of aid to refugees, and at 7:14 a.m., ‘ВЗГЛЯД’ wrote that the Polish president did not intend to put the interests of the Kyiv regime above his own. However, these mentions were isolated, without any connection to the incident on the railway. The materials presented Navrotsky’s position as general political information, without linking it to specific events.

The Russian newspaper was the first to establish an explicit connection, and an hour and twenty minutes later, at 20:02, the Belarusian state channel NEWS.BY picked up and significantly developed this narrative. The NEWS.BY publication broadened the context, presenting the situation as the result of political confrontation within Poland: “After the presidential elections, a dual power structure was established in Warsaw. As soon as Karol Nawrocki from PiS took office as head of state, Tusk’s protégé lost, and the struggle for power only intensified.” The channel added another element of conflict, mentioning that Nawrocki advocates ending support for Ukraine until it recognises the genocide of Poles — the Volhynia massacre.

The pattern of cross-border coordination is obvious: the Russian government channel introduces a new narrative element, and the Belarusian state channel reinforces and develops it an hour and a half later. This is not a coincidence. A time delay of an hour and a half is sufficient for observation, adaptation and publication, but not long enough to consider the events independent. Stylistic and content consistency points to a coordinated strategy.

The function of this narrative shift is multi-layered. The most obvious goal is to shift the focus of attention. The official investigation established that the sabotage was carried out by Ukrainian citizens recruited by Russian special services who crossed the border from Belarus. The narrative about Nawrocki’s decision offers an alternative explanation for the motives: not a Russian special operation, but a reaction by Ukrainians to the cessation of aid to refugees. The creation of a plausible alternative motive blurs the perception of the real attribution.

The second level of function is the split between allies. The narrative exploits three potential lines of conflict: between Poland and Ukraine on the issue of refugees and historical memory, between Tusk and Nawrocki within Polish politics, and between Ukrainian refugees and the Polish leadership. Each line reinforces the impression of destabilisation and chaos, distracting from the centralised operation of the Russian special services.

The third level is the technique of victimisation. The impression is created that Poland is ‘itself to blame’ for what happened: it stopped helping refugees, caused their discontent, and allowed internal political conflicts to destabilise the situation. This technique transforms the country that has been subjected to sabotage into a subject whose actions allegedly provoked the incident. A similar technique was observed in the weather balloon campaign, where Lithuania was accused of hysterical reactions and provocations.

The effectiveness of the technique is based on the use of real facts in a false context. Nawrocki is indeed the president of Poland, and he does have a certain position on Ukrainian issues, including refugees. The exact date of the announcement of the termination of aid requires verification, but the decision itself exists in public discourse. The technique takes these real elements and creates a false causal chain from them. The plausibility of individual facts creates the illusion of credibility for the entire construct.

The psychological mechanisms of effectiveness include multiple cognitive biases. Post hoc ergo propter hoc exploits the natural human tendency to look for causes in previous events. Confirmation bias causes people who are already critical of Ukraine or the Polish authorities to accept the narrative without critical evaluation. The availability heuristic makes recent events more accessible for mental connection, even when such a connection is logically unfounded.

An analysis of alternative explanations for the diversion in the information space revealed a multitude of competing narratives: Navrotsky’s decision on refugees was mentioned three times, the Volhynia massacre four times, transit through Belarus three times, and the dual power of Tusk and Navrotsky once. This multiplicity is not accidental. The creation of several alternative explanations blurs the focus, creates information noise and makes it difficult to form a clear understanding of the real attribution. When the audience is faced with four or five different ‘possible causes,’ the official version about the Russian special services becomes just one of many hypotheses, losing the weight of proven fact.

The coordinated introduction of false causality through the government channels of both countries demonstrates the institutional nature of the technique. This is not a spontaneous interpretation of events by individual commentators, but a coordinated strategy to shift the narrative at a critical moment when the official investigation has identified the real culprits.

The timing of the publication — 18 November, the day of Tusk’s speech in the Sejm with a detailed presentation of the evidence — is no coincidence. The introduction of an alternative explanation at the very moment when the official version received the most detailed confirmation serves to pre-emptively discredit this evidence.

The pattern of coordination between Russian and Belarusian state channels, with a time lag of an hour and a half and the second publication being more substantial, is identical to the mechanisms observed in other phases of the campaign. This confirms the hypothesis of a stable cross-border network, where Russian channels often introduce narrative innovations, and Belarusian channels adapt and amplify them for their audience. The technique of observation-adaptation-amplification creates the impression of organic dissemination of ideas, concealing the coordinated nature of the operation.

Countering the technique of false causality requires an emphasis on the logical structure of the manipulation. Exposing post hoc ergo propter hoc is more effective than refuting specific claims because it teaches the audience to recognise the technique itself, regardless of the content. Demonstrating the lack of factual basis for the connection between Navrotsky’s decision and the sabotage, demanding proof of causality rather than simple temporal sequence, and refocusing on the actual attribution based on the results of the investigation are all elements of a comprehensive countermeasure.

The practical significance of this observation for future incidents is obvious. Introducing alternative explanations by establishing false cause-and-effect relationships is a predictable element of information operations. Knowing the pattern allows counter-narratives to be prepared before manipulative constructs appear. Preemptive exposure of the technique, explanation of the cognitive biases on which it is based, and focusing public attention on rigorous evidence of causality create resilience in the information space to this kind of manipulation.

Methodology

Our research was based on a comprehensive approach to data collection and analysis, ensuring a high degree of reliability of results and the possibility of independent verification of conclusions.

Data collection was carried out between 11 and 18 November 2025, covering eight days before and after the critical incident. The main source of information was the TGStat platform, a professional Telegram channel analytics system that provides access to public posts, metadata, and viewing statistics. We used two sets of keywords to ensure maximum coverage: ‘Warsaw train’ (result: 348 posts) and ‘Warsaw railway’ (result: 525 posts). The data was exported on 19 November 2025 between 01:23 and 01:31 UTC, providing complete coverage of the events of 18 November.

The initial data set contained 873 posts. Deduplication was a critical step in the processing, as some posts were captured by both sets of keywords. We applied strict criteria for identifying duplicates: same channel, identical text in the first 100 characters, and a timestamp within one minute. This process identified and removed 167 duplicates, leaving 706 unique posts from 211 unique channels for further analysis.

The temporal analysis included several levels of data grouping. At the macro level, posts were grouped by day to identify the overall dynamics of the campaign. At the meso level, grouping by hour was used to detect daily activity patterns. At the micro level, grouping by minute was used to detect synchronisation. Phase classification was based on a combination of time boundaries and thematic shifts: Phase 1 covered the entire day of 17 November, Phase 2 covered the period from 10:25 to 15:45 on 18 November, Phase 3 covered the critical fifteen minutes from 15:46 to 16:00, Phase 4 covered evening activity from 16:00 to 23:55.

Content analysis employed multiple methods. Keyword extraction used frequency analysis to identify the most frequently used terms. Co-occurrence analysis identified connections between different concepts. Identification of mood markers determined the emotional tone of messages. Detection of sarcasm indicators focused on the use of emojis, quotation marks, and rhetorical constructions. Rhetorical analysis included the identification of frames, the classification of manipulative techniques, and comparison with historical patterns.

Network coordination analysis used several approaches. Temporal clustering identified groups of posts published within narrow time windows. Common phrase analysis detected identical or nearly identical wording across different channels. The identification of cross-border connections focused on coordination between Russian and Belarusian sources. The detection of public-private connections identified interactions between official and unofficial channels.

To assess temporal synchronisation, a sliding window with intervals of one, five, and fifteen minutes was used. Statistical significance was determined through binomial distribution, and the probability of random coincidence was calculated for each cluster of synchronous publications.

The analysis of Belarusian-Russian coordination included several measurements. Comparison of samples revealed identical patterns of sarcasm, use of emojis, and quotation marks. Temporal correlation analysis determined the delays between publications by Russian channels and the Belarusian state source. The identification of linguistic markers focused on the use of the forms ‘Belorussia’ versus ‘Belarus’ as indicators of ideological positioning. A comparison of state and private channels revealed differences in the behaviour of official and unofficial sources.

The detection of absurdisation used structural analysis to identify the transformation from ‘complex → crude’. Linguistic markers included emojis, rhetorical questions, and other signals of sarcasm. Comparison with historical samples showed the stability of the technique over time.

Phase classification was based on defining temporal boundaries between phases, thematic clustering of content, detection of rhetorical shifts, and analysis of audience engagement patterns.

The level of confidence in the conclusions is differentiated by category. High confidence (95%) is assigned to four key findings. The four-phase structure is confirmed by both temporal and thematic clustering. Belarusian-Russian coordination has an error probability of less than 0.001 based on sample comparison. The technique of absurdisation is proven through structural analysis and historical comparison. The anticipatory nature of the campaign is documented through a thirty-hour lead time.

Medium confidence at 75% applies to three aspects. The specific mechanisms of coordination remain a matter of inference, as we cannot distinguish with complete certainty between observation and direct instructions. The exact reach outside Telegram cannot be determined, as views are cumulative and not tied to a specific time. The motivations of individual channels are derived from behavioural patterns but cannot be confirmed directly.

Some aspects remain unknown. Coordination in private groups and chats is not visible in the public sphere. Financial flows between channels are not available for analysis. The presence or absence of a direct state order cannot be determined, as self-coordination may appear identical.

The reproducibility of the results is ensured by the complete openness of the data and methods. The source data is available in CSV format with 706 posts and complete metadata. The processing scripts are written in Python using the pandas and matplotlib libraries. The analytical notebooks are presented in Jupyter format for step-by-step reproduction of the analysis. Visualisations are exported in PNG format for use in presentations and publications.

Conclusions and implications

Our research has revealed several critical findings that have significant implications for understanding modern information warfare and developing countermeasures.

The first key finding concerns the nature of the information campaign. We are not dealing with reactive outrage or spontaneous responses to events, but with a pre-planned, proactive campaign with a clear temporal structure. The first phase begins thirty hours before any official accusations are made, creating a ready-made interpretative framework. The third phase responds in just seven minutes to the prime minister’s detailed statement, which would be impossible without constant monitoring. The fourth phase is sustained by eight hours of continuous evening activity, demonstrating the consistency characteristic of organised operations. These characteristics point to institutional capabilities rather than a spontaneous reaction.

The second key finding relates to cross-border Belarusian-Russian coordination. The Belarusian state channel NEWS.BY demonstrates identical patterns to Russian channels, publishing its messages with a four-hour delay. This indicates a decentralised model of coordination, where monitoring the actions of Russian channels leads to the adaptation of their patterns by the Belarusian state source. The integration of public-private networks creates cycles of legitimisation, where private channels create narratives and state channels validate them. Cooperation in cross-border information warfare demonstrates a qualitatively new level of coordination. The probability of a random coincidence of all observed patterns is less than one thousandth, which mathematically proves the existence of coordination.

The third finding focuses on the technique of absurdisation as the main tool for discrediting evidence. Ten specific facts presented by Tusk were reduced to the sarcastic phrase ‘He didn’t swing a piece of rail 🙂’. The systematic use of this technique in numerous cases over nineteen years indicates a repeating pattern. There is an accumulation of institutional knowledge about which techniques work effectively. The refinement of the technique is evident in faster responses and more sophisticated wording.

The fourth finding concerns the pre-emptive nature of the information war. Predictions appear thirty hours before official accusations are made, allowing a ready-made interpretative framework to be created. After the real accusations appear, the audience, having been primed, perceives them as confirmation of the initial ‘predictions.’ This creates a mindset of rejecting evidence even before it has been examined in detail.

The fifth finding documents the scale of sustained mobilisation. Seven hundred and six posts from two hundred and eleven channels over seven days represent a significant operation. Two hundred and forty-four posts on the critical day of 18 November demonstrate the ability to concentrate efforts. One hundred and twenty-eight posts in one evening show consistency rather than a temporary surge in activity.

The implications for information security are multifaceted. The predictability of the four-phase structure allows for the development of counter-preparation strategies. When the first phase is detected, the subsequent phases two, three and four can be predicted with a high degree of certainty. Counter-narratives can be prepared in advance, even before the appearance of absurd and conspiratorial messages. Warning the audience about upcoming manipulative techniques proves to be more effective than subsequent refutation.

Cross-border coordination requires a regional response. Belarusian-Russian cooperation points to the need to strengthen cooperation in the field of information security between the Baltic states and Poland. The creation of common monitoring systems will make it possible to detect coordinated campaigns at an early stage. Coordinated counter-messaging will enhance the effectiveness of countermeasures. Joint training for fact-checkers and journalists will improve the quality of exposure of manipulation.

Platform policies need to be updated to effectively counter coordination. Detecting temporal synchronisation can automatically identify suspicious clusters of publications. Cross-border network analysis will allow tracking coordination between sources from different countries. Monitoring links between public and private channels will reveal narrative validation cycles. Policies against coordinated inauthentic behaviour must adapt to new forms of coordination.

Countering the technique of absurdisation requires specialised approaches. Traditional fact-checking, which focuses on refuting specific statements, is insufficient against absurdisation. It is necessary to expose the technique itself as a manipulative technique, explaining its mechanism to the audience. Demonstrating historical examples of the technique’s use in a variety of cases shows its systematic nature. Meta-criticism, i.e., criticism of the method of manipulation rather than entering into a debate on the substance of the claim, undermines the technique’s effectiveness. Educating the audience about manipulative techniques creates long-term resilience.

Threats to democratic discourse require serious attention. The systematic devaluation of evidence creates epistemic closure, where a significant portion of the audience is convinced that nothing can serve as evidence. This leads to a sense of futility in investigations and undermines the motivation to collect and present evidence. Public cynicism develops, where all evidence is a priori perceived as false or fabricated.

Pre-emptive disinformation is particularly dangerous. Creating narratives before the facts emerge inoculates the audience against future evidence. Self-fulfilling prophecies create the illusion that the initial predictions were correct. Control over the framing of events before their official coverage determines the interpretation of facts by a significant portion of the audience.

Cross-border coordination without centralised control demonstrates high resilience. The absence of a single point of failure makes the system more viable. The ability to adapt through observation and correction increases efficiency. The integration of the public and private sectors creates cycles of narrative legitimisation.

Algorithmic amplification of coordinated engagement exploits the basic mechanisms of social platforms. Artificial signals of popularity through coordinated likes and comments deceive recommendation systems. Manipulation of algorithms leads to organic users seeing content with preloaded positive or negative reactions, which influences their perception.

Recommendations for various stakeholders follow from the analysis. Researchers should create libraries of samples for proactive detection of manipulative campaigns, develop cross-border information space monitoring systems, create training programmes for recognising absurdification techniques, and openly share data sets for independent verification of conclusions.

Social media platforms should implement systems to detect temporal synchronisation of posts, flag coordinated absurdisation as a form of manipulation, track cross-border public-private networks, and publish transparency reports on detected information operations.

Governments should develop pre-incident prevention strategies rather than limiting themselves to post-facto refutation, strengthen regional cooperation on information security, support independent fact-checking organisations, and build audience resilience through media literacy programmes.

Journalists should expose manipulative techniques rather than merely refuting specific content, provide historical context for the use of patterns in past cases, emphasise the specificity and concreteness of evidence, and refrain from amplifying absurd narratives through uncritical reporting.

The audience must learn to recognise anticipatory narratives such as ‘they will accuse X’, question the wholesale rejection of evidence, check content for patterns of absurdity, and cross-check information from multiple independent sources.

The significance for the Baltic-Polish region is particularly relevant. Geographical proximity makes Poland and the Baltic states the front line of information confrontation. The critical importance of transport routes, including railway infrastructure for NATO logistics, makes them likely targets for future information operations. Historical patterns suggest that the same techniques will be used in future incidents. The Belarusian-Russian coordination that has been detected points to broader cooperation covering a wide range of areas.

The threat level for the region is assessed as medium-high with regard to similar operations targeting Baltic railway infrastructure, Polish-Ukrainian logistics, NATO supply routes and critical infrastructure in general.

Concluding thoughts highlight several key characteristics of modern information warfare. It is proactive rather than reactive, allowing perceptions of events to be shaped before they occur. It is coordinated across borders rather than limited to a single country, creating complex networks of influence. It is based on sustainable patterns rather than being spontaneous, demonstrating institutional learning. It is detectable rather than invisible, creating opportunities for countermeasures.

The four-phase structure, Belarusian-Russian coordination, and absurdisation techniques are systematic and predictable phenomena. It is precisely this predictability that becomes the system’s vulnerability. Knowledge of patterns allows counter-strategies to be prepared before incidents occur, turning reactive countermeasures into proactive ones.

Data-driven analysis is critical for evidence-based policy development, effective counter-messaging, platform accountability, and raising public awareness of manipulative techniques. Without systematic monitoring and rigorous analysis, the information space remains vulnerable to manipulation.

Transparency of research methods, reproducibility of results, and international cooperation in sharing data and findings are key to building the resilience of the information space in democratic societies.